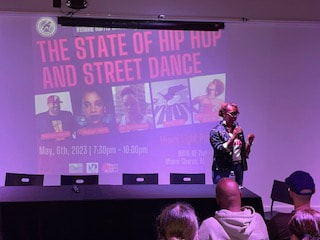

I’m still ruminating on all the pearls of wisdom dat was brought forth. Yawwwww, it was like a celebrity scholar event. I have included both women’s scholarship in my qualifying exam (for my phd program) and mi bookshelf full up of all ah dem books and ting. I can’t believe that I had this opportunity! Well, as soon as mi pull up to di Perez Art Museum Miami, di Dancehall music was lickin’ off. I couldn’t wait to get inside and feel di vibz. I smiled deeply as I parked my car and started choregraphing my entrance. I walked up the stairs and the bass got deeper and deeper. When I cut the corner, I bumped into Marie Vickles, The Senior Director of Education at the Perez and asked her whatagwan, when she informed me that it was dead, I was gagged. When I walked over, I saw the selector and cultural curator Jason Panton killin’ it but he was spinnin’ to an empty house. I was in disbelief. How dem a waste dis gud music? SHAMEFULL. There were a handful of people outside. Two Black women were standing, dancing, and filming themselves. There was a table of men and women just sitting there; wah dis fada? Then, I saw a waiter walk out of the restaurant to do a dip and bounce. I had seen enough and headed to the talk inside the museum.

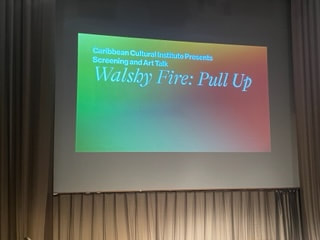

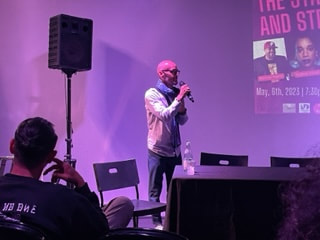

I walked in the auditorium, surveyed the space, and looked for a familiar face. I saw Jamaican-American Filmmaker Alicia G. Edwards (see my post on Walshy Fire: Pull Up) and Kei Miller, Jamaican Professor and Creative Writer, I sat next to him. Dr. Hope and Dr. Saunders were introduced by Vickles and then it began. Nuggets upon nuggets were dropped. The discussion began with a breakdown of the title of Saunders’ first chapter “Is Not Everything Good to Eat, Good to Talk.” Then Saunders decimated di place when she stated “Popular culture is sophisticated and well informed, more so than academia” (Saunders 2024). And those that know know…mic drop!

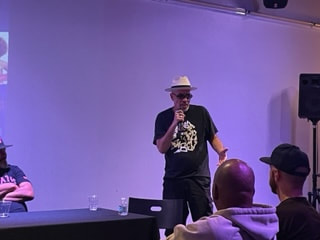

They discussed consumption, agency and how women “have the power to demand and command their power” YASSS! Saunders referred to Vybz Kartel as the pum pum laureate and both Hope and Saunders went into a deep analysis of his work, lyrics, tattoo culture, and the skin bleaching phenomenon. They were tag teaming each other with their brilliance and knowledge. I really connected to the ideology of “using the body as a canvas”, “taking control of the narrative and reclaiming power,” “resisting and rejecting power through the body”, “controlling the narrative”, and “telling your story through the canvas of the skin [and movement]”. I was literally in a knowledge candy store! ALL OF THIS IS CONNECTED TO MY DISSERTATION RESEARCH!!!

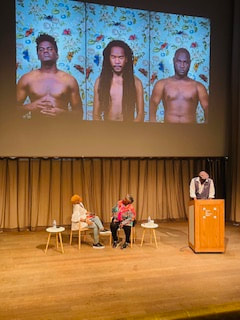

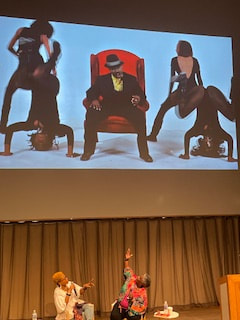

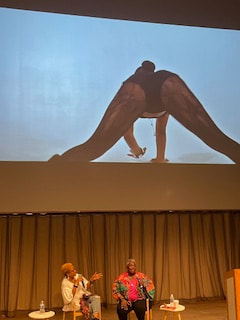

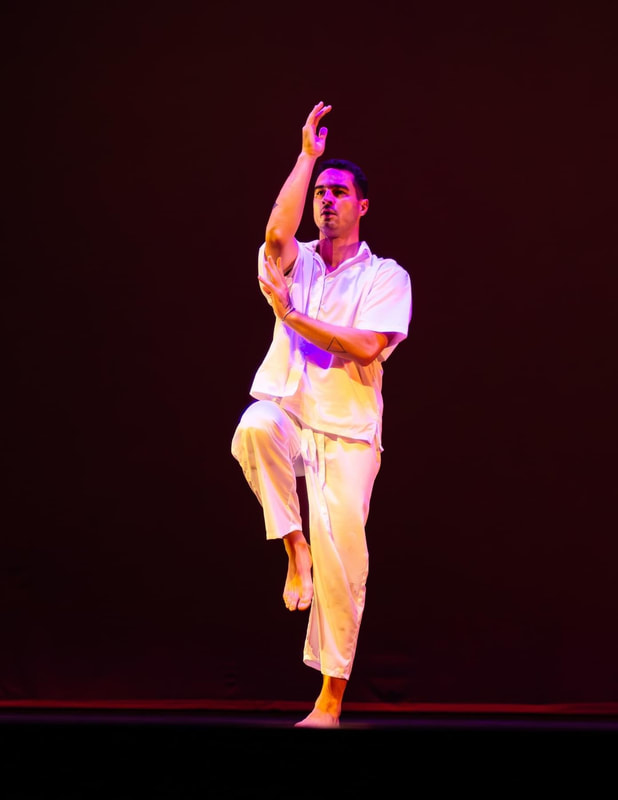

Saunders shared videos off Dancehall artist Vybz Kartel, Jamaican visual artist Ebony Patterson, and Dancehall artist Spice. Kei Miller closed with a reading of Ebony G. Patterson’s “While The Dew Is Still On the Roses”, a video played in the background which featured three shirtless Black men performing various gestures, getting dressed and fixing their hair. It was powerful piece which Kei read with both pride and tenderness, drawing us into the spectacle and spectacular Black male body.

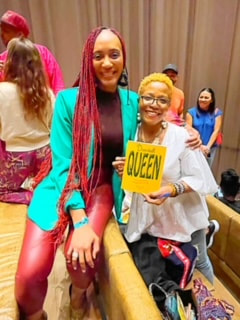

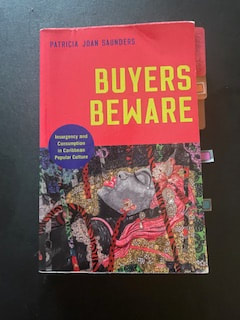

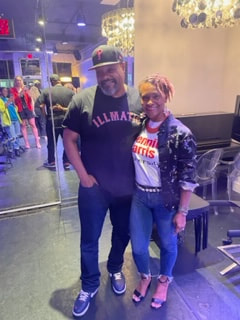

The floor opened for questions and then book signings and pictures. I have two Buyers Beware… books already so you can purchase one. It will change your life. I gifted myself with Dr. Hope’s latest offering Dancehall Queen: Erotic Subversion which she coedited with Carla Lamoyi. The book is written in both English and Spanish. Gawd is gudt!!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed