Introduction

Professor Kieron Sargeant invited me to the 15th annual COCO Dance Festival in Trinidad and Tobago as the Dance Writer in Residence, a position made possible by the Skidmore College Travel to Read Grant. Kieron and I spoke in June about the possibility of me reviewing his work at the Festival. During the conversation, we addressed the state of dance writing in the United States, which included 1. the lack of quality dance pre/reviews that articulated the breadth, depth, and nuances of dancers/dances of the African Diaspora and 2. the complete avoidance and erasure of the work of these artists by local/regional reviewers. We also shared what I could offer the Trinidadian community in terms of my dance writing and cultural critique. When Kieron messaged me in September to confirm the trip, I began to think deeply about what I wanted to write about, how that information would be disseminated, and how this project demonstrated a new model of dance writing, one that includes traveling to countries in the Caribbean Diaspora and engaging in autoethnography/ethnography to include participant-observation, interviews, tours, shopping, food, and culture. I was elated at all the possibilities!

I quickly realized that this trip was going to be rich. I was overwhelmed and immediately began strategizing how to get the information (ethnographic details, historical references, dance writing, interviews, and cultural critique) out in real time without sacrificing all the details. I decided that I would publish my daily ethnographic notes on my Facebook page and publish the dance writing in 5 editorial pieces. The articles will feature interviews with Trinidadian artist/scholar Kieron Sargeant, Co-founders of COCO Dance Festival Sonja Dumas, and Dave Williams, The President of The National Dance Association of Trinidad and Tobago, Ms. Emelda Lynch-Griffith, and American artist/scholar Trent Williams Jr. as well as dance reviews of the two performances at The National Academy for the Performing Arts.

Who is Kieron Sargeant?

My interview with Kieron took place over Zoom and as per usual, it was lively, funny, and thoughtful. I asked Kieron several questions ranging from his background and dance and family history to the state of dance education and support (government and community) in the country. Kieron shared his challenges growing up in a rough or marginalized community, the gender politics concerning male dancers, bullying he endured leaving the “rehearsal center to head home” (Sargeant 2023), and the support his grandmother offered during these incidents, “She used to go out in the road and cuss dem stink” (Sargeant 2023). Kieron’s humor, coupled with his transparency created a flowing, effortless conversation. I learned about the Prime Minister's Best Village Trophy Competition and his role as dance instructor and performer (dancer and drummer). With his strong folklore roots under his belt, he received a scholarship from the government to study dance and dance education at UWI (University of the West Indies). After the completion of his studies there, he was employed with the ministry as a dance education teacher and remained there until 2017 when he entered the graduate program in Dance at Florida State University in Tallahassee.

Kieron provided a deep analysis about his experiences as a professor at Florida Atlantic Mechanical University (FAMU) in Tallahassee and The University of Iowa as well as his observations attending conferences nationally and internationally. He discussed the colonial behaviors that dictate a certain decorum in the studio which does not lend itself to inclusion, feeling welcomed, and the sense of freedom and community that he felt during his training at home in Trinidad. These experiences influenced his teaching philosophy which includes “disseminating the traditional dance forms of the Caribbean to the space” (Sargeant 2023).

As a traditionalist, Kieron shared an ideology or technique that is based on “aged bodies,” where he claims that “there is a particular way that the body moves. So, I have adapt[ed] that way of moving and that is how I teach. The kind of like old way. Cause when I use the skirt. I don’t use the skirt like everyone else in Trinidad. I have a way how I use the skirt because it’s from the teaching of elders. No young person didn’t teach me it. Elders taught me. And they were the ones who put me to sit down and have conversation[s] with [them] and talk about the form and how the form is done, and I continue with that, and it works for me in the space and even internationally [as well]” (Sargeant 2023).

Kieron’s passion for dance is evidenced in his very colorful perspective concerning the appropriation of Caribbean dance stating, “You give di people dem dey credit” (Sargeant 2023) as well as the lack of authenticity which brings up questions such as: what is Caribbean dance, who is qualified to teach it, the issues concerning traditional versus fusion forms, how Caribbean dance is described as a course in academia, and just all di wrong tings!

As an advocate for dance education in Trinidad, while at Florida State, he “wanted to find a way for the university to come to Trinidad to present work” (Sargeant 2023) and dancers to come to the university to pursue graduate degrees, but this idea also posed several challenges, which included students securing a visa which impacted them attending the audition. Through tremendous support at FSU, the exchange program began in 2018 to conduct an international audition during the COCO Dance Festival. This lasted for 2 years but due to COVID it stopped and wasn’t reinstituted.

Prior to this, his relationship with COCO commenced in 2013, beginning as a guest artist performing traditional dances, then later becoming an instructor teaching master classes. He decided he wanted to broaden his involvement so, while teaching at the University of Iowa in 2022, he decided to submit a work for the first time. This year was important for several reasons, 1. it was the 15th year celebration of COCO, 2. A critic and dance reviewer was invited to write about the festival; and 3. this was a great opportunity for Jaruam Xavier, the Brazilian co-collaborator to share his work “Ori” on an international stage.

“Ori” Review

Kieron shared the first time he saw Jaruam perform “Ori” at The University of Iowa where Jaruam is a graduate student, and how he was immediately intrigued by Jaruam’s physical prowess and the context of the piece. They discussed the premise of the work which focuses on the seven sketches and the similarities between Brazilian Candomblé and the Orisha’s in Trinidad. Together, a partnership was developed. Kieron offered his insight, helping him abstract elements of the work and assisting with choreographic sequencing.

After viewing the piece, I immediately understood Kieron’s interest. Here is my review:

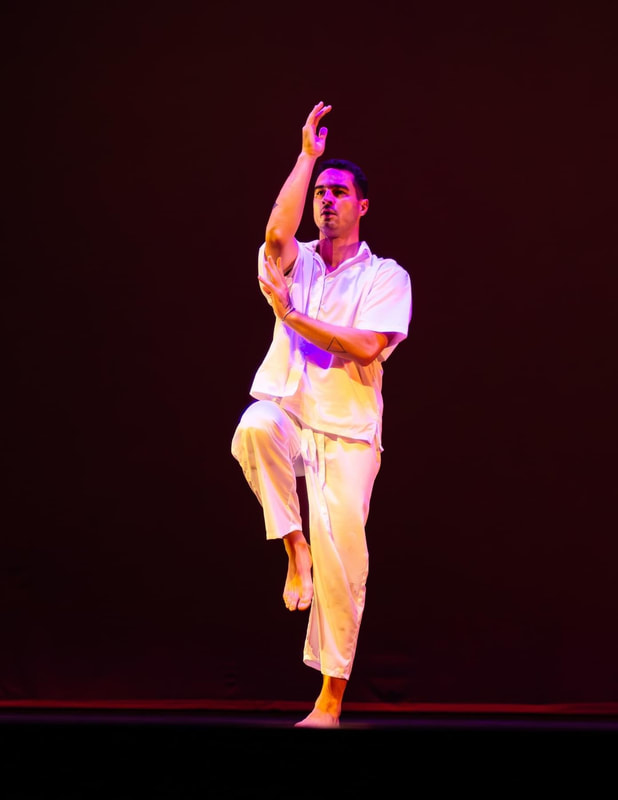

Dancer, Jaruam Xavier begins “Ori” stage left wearing a white loose top and flowing pants. The lighting is dim and red. As the music envelops, chimes and the bells set the tone, calming the spirit. Jaruam is crouched over saluting the earth. He gently touches the floor with his hand, elbow, and then his head. He transitions into a seated position, touching the ground with his forehead, then alternates his hands to touch his crown. Lowering his body to a seated position with his legs extended downstage left, he reaches behind himself. Our eyes follow intensely. This beautiful ritual is captivating, drawing the viewer into the sacred and personal expressions of worship. As an elegant gazelle, Jaruam shifts his body side to side, never neglecting his hand/head motif. Carving space, searching for, and receiving the ancestral spirit—he is anointed.

His movement is soft, and fluid juxtaposed with a rich fullness that includes Brazilian capoeira, tai chi, yoga, contemporary, and release techniques. As the sound increases, the instrumentation shifts, reminiscent of a Brazilian rain forest. I hear thunderclap, horses neighing, rain falling, and jaguars and leopards growling, defending their territory.

Jaruam is agile and focused. His big circular movements are clean and precise as he accesses the ancestors, clearing pathways. When the spirits are connected, the energy is high; he jumps, leaps, turns, spins, rolê: (roll), and Aú (cartwheel) across the floor. As the ancestors assemble, there is a shift in energy and focus.

Standing, facing stage right, he cleanses his body, brushing down and out, sending the energy away into the atmosphere. As he concludes his ritual, the floor turns a beautiful shade of blue. He travels the course straight across the stage as if he were a boat skipping across the beautiful Caribbean Sea binding him to the Orisha’s in Cuba.

The tone and texture of both the movement and sound shifts, indicating that Jaruam may have entered another realm or accessed another spirit. He contorts, sweeps, unfolds, and explodes, bringing the energy in and releasing it seamlessly. The cleansing, brushing down and out movements return, this time he is facing the audience. His movement slows, and he embodies an animal. Concaving on the floor, his chest undulates while his head snakes side to side like new born mammal searching for the warmth of its mother. And, in the next breath, he transforms to an angelic ethereal being, spreading his divine holy particles into the atmosphere. Arms flailing, chest open, legs extended to the ceiling in a handstand, our breath is paused, we are listening with our eyes and ears. My skin tingles as the image of the statue of Christ the Redeemer appears ascending to the heavens while he moves through the space. The light dims. This man is a conduit, overseeing and transcribing the orders of the saints through his body.

Conclusion

We concluded our interview discussing the importance of dance writing and the state of dance education and performance in Trinidad and Tobago. This included the need for professional development for teachers: continuing education, attending conferences nationally and internationally, presenting papers, teaching at conferences, inviting people into the space to talk about dance and providing workshops for dance educators, going to see local dance groups, and going to other countries to observe their dance culture.

With great conviction, Kieron expressed the need for government support, “we need to get the support from the Ministry of Culture in Trinidad and Tobago. You need to get support from them…to help the space to develop. I think that the lack of support is what’s causing this space to kind of collapse. We have a diverse pool of dance that we want to share to the world, and we need the support to share it” (Sargeant 2023).”

Final Thoughts

One of the goals that I have as a dance writer and cultural critic is to pique the interest of the community so that people become interested in dance, are going to see dance consistently, prioritizing dance, WRITING about it, talking about it, and are supporting it monetarily.

Part 2 coming soon!

Image Credits:

Head Shot: Maximo Media

Ori: Karen Johnstone’s Photography

Dance Workshop: Karen Johnstone’s Photography

Professor Kieron Sargeant invited me to the 15th annual COCO Dance Festival in Trinidad and Tobago as the Dance Writer in Residence, a position made possible by the Skidmore College Travel to Read Grant. Kieron and I spoke in June about the possibility of me reviewing his work at the Festival. During the conversation, we addressed the state of dance writing in the United States, which included 1. the lack of quality dance pre/reviews that articulated the breadth, depth, and nuances of dancers/dances of the African Diaspora and 2. the complete avoidance and erasure of the work of these artists by local/regional reviewers. We also shared what I could offer the Trinidadian community in terms of my dance writing and cultural critique. When Kieron messaged me in September to confirm the trip, I began to think deeply about what I wanted to write about, how that information would be disseminated, and how this project demonstrated a new model of dance writing, one that includes traveling to countries in the Caribbean Diaspora and engaging in autoethnography/ethnography to include participant-observation, interviews, tours, shopping, food, and culture. I was elated at all the possibilities!

I quickly realized that this trip was going to be rich. I was overwhelmed and immediately began strategizing how to get the information (ethnographic details, historical references, dance writing, interviews, and cultural critique) out in real time without sacrificing all the details. I decided that I would publish my daily ethnographic notes on my Facebook page and publish the dance writing in 5 editorial pieces. The articles will feature interviews with Trinidadian artist/scholar Kieron Sargeant, Co-founders of COCO Dance Festival Sonja Dumas, and Dave Williams, The President of The National Dance Association of Trinidad and Tobago, Ms. Emelda Lynch-Griffith, and American artist/scholar Trent Williams Jr. as well as dance reviews of the two performances at The National Academy for the Performing Arts.

Who is Kieron Sargeant?

My interview with Kieron took place over Zoom and as per usual, it was lively, funny, and thoughtful. I asked Kieron several questions ranging from his background and dance and family history to the state of dance education and support (government and community) in the country. Kieron shared his challenges growing up in a rough or marginalized community, the gender politics concerning male dancers, bullying he endured leaving the “rehearsal center to head home” (Sargeant 2023), and the support his grandmother offered during these incidents, “She used to go out in the road and cuss dem stink” (Sargeant 2023). Kieron’s humor, coupled with his transparency created a flowing, effortless conversation. I learned about the Prime Minister's Best Village Trophy Competition and his role as dance instructor and performer (dancer and drummer). With his strong folklore roots under his belt, he received a scholarship from the government to study dance and dance education at UWI (University of the West Indies). After the completion of his studies there, he was employed with the ministry as a dance education teacher and remained there until 2017 when he entered the graduate program in Dance at Florida State University in Tallahassee.

Kieron provided a deep analysis about his experiences as a professor at Florida Atlantic Mechanical University (FAMU) in Tallahassee and The University of Iowa as well as his observations attending conferences nationally and internationally. He discussed the colonial behaviors that dictate a certain decorum in the studio which does not lend itself to inclusion, feeling welcomed, and the sense of freedom and community that he felt during his training at home in Trinidad. These experiences influenced his teaching philosophy which includes “disseminating the traditional dance forms of the Caribbean to the space” (Sargeant 2023).

As a traditionalist, Kieron shared an ideology or technique that is based on “aged bodies,” where he claims that “there is a particular way that the body moves. So, I have adapt[ed] that way of moving and that is how I teach. The kind of like old way. Cause when I use the skirt. I don’t use the skirt like everyone else in Trinidad. I have a way how I use the skirt because it’s from the teaching of elders. No young person didn’t teach me it. Elders taught me. And they were the ones who put me to sit down and have conversation[s] with [them] and talk about the form and how the form is done, and I continue with that, and it works for me in the space and even internationally [as well]” (Sargeant 2023).

Kieron’s passion for dance is evidenced in his very colorful perspective concerning the appropriation of Caribbean dance stating, “You give di people dem dey credit” (Sargeant 2023) as well as the lack of authenticity which brings up questions such as: what is Caribbean dance, who is qualified to teach it, the issues concerning traditional versus fusion forms, how Caribbean dance is described as a course in academia, and just all di wrong tings!

As an advocate for dance education in Trinidad, while at Florida State, he “wanted to find a way for the university to come to Trinidad to present work” (Sargeant 2023) and dancers to come to the university to pursue graduate degrees, but this idea also posed several challenges, which included students securing a visa which impacted them attending the audition. Through tremendous support at FSU, the exchange program began in 2018 to conduct an international audition during the COCO Dance Festival. This lasted for 2 years but due to COVID it stopped and wasn’t reinstituted.

Prior to this, his relationship with COCO commenced in 2013, beginning as a guest artist performing traditional dances, then later becoming an instructor teaching master classes. He decided he wanted to broaden his involvement so, while teaching at the University of Iowa in 2022, he decided to submit a work for the first time. This year was important for several reasons, 1. it was the 15th year celebration of COCO, 2. A critic and dance reviewer was invited to write about the festival; and 3. this was a great opportunity for Jaruam Xavier, the Brazilian co-collaborator to share his work “Ori” on an international stage.

“Ori” Review

Kieron shared the first time he saw Jaruam perform “Ori” at The University of Iowa where Jaruam is a graduate student, and how he was immediately intrigued by Jaruam’s physical prowess and the context of the piece. They discussed the premise of the work which focuses on the seven sketches and the similarities between Brazilian Candomblé and the Orisha’s in Trinidad. Together, a partnership was developed. Kieron offered his insight, helping him abstract elements of the work and assisting with choreographic sequencing.

After viewing the piece, I immediately understood Kieron’s interest. Here is my review:

Dancer, Jaruam Xavier begins “Ori” stage left wearing a white loose top and flowing pants. The lighting is dim and red. As the music envelops, chimes and the bells set the tone, calming the spirit. Jaruam is crouched over saluting the earth. He gently touches the floor with his hand, elbow, and then his head. He transitions into a seated position, touching the ground with his forehead, then alternates his hands to touch his crown. Lowering his body to a seated position with his legs extended downstage left, he reaches behind himself. Our eyes follow intensely. This beautiful ritual is captivating, drawing the viewer into the sacred and personal expressions of worship. As an elegant gazelle, Jaruam shifts his body side to side, never neglecting his hand/head motif. Carving space, searching for, and receiving the ancestral spirit—he is anointed.

His movement is soft, and fluid juxtaposed with a rich fullness that includes Brazilian capoeira, tai chi, yoga, contemporary, and release techniques. As the sound increases, the instrumentation shifts, reminiscent of a Brazilian rain forest. I hear thunderclap, horses neighing, rain falling, and jaguars and leopards growling, defending their territory.

Jaruam is agile and focused. His big circular movements are clean and precise as he accesses the ancestors, clearing pathways. When the spirits are connected, the energy is high; he jumps, leaps, turns, spins, rolê: (roll), and Aú (cartwheel) across the floor. As the ancestors assemble, there is a shift in energy and focus.

Standing, facing stage right, he cleanses his body, brushing down and out, sending the energy away into the atmosphere. As he concludes his ritual, the floor turns a beautiful shade of blue. He travels the course straight across the stage as if he were a boat skipping across the beautiful Caribbean Sea binding him to the Orisha’s in Cuba.

The tone and texture of both the movement and sound shifts, indicating that Jaruam may have entered another realm or accessed another spirit. He contorts, sweeps, unfolds, and explodes, bringing the energy in and releasing it seamlessly. The cleansing, brushing down and out movements return, this time he is facing the audience. His movement slows, and he embodies an animal. Concaving on the floor, his chest undulates while his head snakes side to side like new born mammal searching for the warmth of its mother. And, in the next breath, he transforms to an angelic ethereal being, spreading his divine holy particles into the atmosphere. Arms flailing, chest open, legs extended to the ceiling in a handstand, our breath is paused, we are listening with our eyes and ears. My skin tingles as the image of the statue of Christ the Redeemer appears ascending to the heavens while he moves through the space. The light dims. This man is a conduit, overseeing and transcribing the orders of the saints through his body.

Conclusion

We concluded our interview discussing the importance of dance writing and the state of dance education and performance in Trinidad and Tobago. This included the need for professional development for teachers: continuing education, attending conferences nationally and internationally, presenting papers, teaching at conferences, inviting people into the space to talk about dance and providing workshops for dance educators, going to see local dance groups, and going to other countries to observe their dance culture.

With great conviction, Kieron expressed the need for government support, “we need to get the support from the Ministry of Culture in Trinidad and Tobago. You need to get support from them…to help the space to develop. I think that the lack of support is what’s causing this space to kind of collapse. We have a diverse pool of dance that we want to share to the world, and we need the support to share it” (Sargeant 2023).”

Final Thoughts

One of the goals that I have as a dance writer and cultural critic is to pique the interest of the community so that people become interested in dance, are going to see dance consistently, prioritizing dance, WRITING about it, talking about it, and are supporting it monetarily.

Part 2 coming soon!

Image Credits:

Head Shot: Maximo Media

Ori: Karen Johnstone’s Photography

Dance Workshop: Karen Johnstone’s Photography

RSS Feed

RSS Feed